In this blog post, I delve into the research conducted by Fabian W. Otte, Sarah-Kate Millar, and Stefanie Klatt, exploring their “Periodization of Skill Training” framework (“PoST”) through the lens of basketball shooting development. With their consent, this blog offers an interpretation of their work, aiming to adapt their theoretical insights and practical applications to the context of basketball. By applying the principles of the “PoST” framework to basketball shooting, I aim to provide coaches and practitioners in the basketball community with a structured approach to skill training periodization and planning. Through this adaptation, I seek to empower basketball coaches to optimize their training environments and facilitate the development of effective shooting skills in their players.

In basketball, as in other team sports, the value of organized training sessions led by coaches is widely acknowledged to enhance athlete development and readiness for competitive environments (Hodges and Franks, 2002; Côté et al., 2007). These sessions, often conducted with full teams, small groups or on an individual basis, are deemed most effective for skill acquisition when they mirror the complex dynamics of actual game situations (Davids et al., 2008; Renshaw et al., 2019a). However, there’s a growing trend in performance sports toward specialized coaching, where individual or small group sessions are led by “specialist coaches” (Smith, 2018) like basketball shooting coaches . While common in sports like baseball and American Football, specialized coaching roles in basketball, such as shooting coaches, have gained traction only recently (e.g., BBC, 2018; Smith, 2018; Austin, 2019). Supporting these specialist coaches with modern scientific principles in skill training planning is crucial.

The limited number of athletes involved in these sessions can hinder full representation of game demands, potentially restricting exploration of action opportunities. To avoid a shift back to traditional coaching methods, which often rely on intuition and historical practices but little evidence based coaching (Williams and Ford, 2009), it’s important to address certain pitfalls associated with traditional coaching, such as limited performance variability, disconnected movement from game contexts, and repetitive technical drills (Passos et al., 2008; Stolz and Pill, 2014; Renshaw et al., 2009).

Acknowledging the need for research-backed coaching methodologies, recent efforts have focused on skill training periodization, exemplified by the Skill Acquisition Periodization (SAP) framework. Developed by Farrow and Robertson (2017), SAP adapts physiological periodization principles into skill training concepts, making them accessible to coaches. While SAP effectively breaks down training aspects like specificity and progression, coaches at different levels may face challenges such as limited access to equipment and time constraints.

Farrow and Robertson’s strategies for longitudinal skill training, while beneficial for team coaches preparing for extended periods, may not fully suit specialists who work with athletes for shorter durations, like “specialist coaches.” In response, the Periodization of Skill Training (PoST) framework, developed by Fabian Otte and his colleagues, aims to integrate monitoring principles from the SAP model, providing a model for skill development tailored to specialist coaching scenarios. Additionally, game-based approaches (GBAs) offer holistic skill learning frameworks, emphasizing learner-centered approaches through modified games.

While GBAs are valuable for team training, their applicability to specialist coaching is limited. Thus, the PoST framework is proposed to address individualized training, focusing on skill levels, training environments, and game demands. The original PoST framework is structured into three parts, and I’ll be staying true to that concept: skill training theory, the PoST framework, and its application to training planning. Throughout, the context of basketball shooting development is used to illustrate the framework’s implementation due to its specialist nature and the prevalence of traditional coaching methods, which may hinder skill development.

PART A: SKILL TRAINING THEORY AND RESEARCH

To bridge academic knowledge with practical coaching, this section briefly examines the constraints-led approach (CLA) in skill training and introduces three key challenges for coaches in managing the training environment.

CLA as a Theoretical Account on Basketball Shooting Development

The CLA, rooted in dynamical systems, ecological psychology, and non-linear pedagogy, offers insights into skill acquisition and training periodization (Renshaw and Chow, 2019; Renshaw et al., 2019b). It views athletes within open systems, like basketball shooters, as dynamically interacting with their environment (Pinder et al., 2011; Renshaw et al., 2016). For basketball shooters, tasks like shooting a jump shot depend on complex constraints, including opponent defense, teammates and tactics, and individual factors (Davids, 2012, 2015; Correia et al., 2019; Renshaw et al., 2019b). This dynamic interaction implies that shooting situations are ever-changing, demanding adaptability and constant coupling of perception and action from shooters (Newell, 1986; Renshaw et al., 2010). The CLA emphasizes athletes’ ability to adapt their movements to varying constraints and to couple information with actions (Bernstein, 1967; Gibson, 1979, 2019; Renshaw et al., 2010). This perspective underscores the importance of coaches in manipulating task constraints to facilitate athletes’ exploration and learning within the training environment (Renshaw et al., 2016).

The primary skill that basketball shooters should be practicing is “Adaptability”. Most bad shooting habits cause players to be less adaptable, thereby limiting their success. Traditional coaching methods that focus on large amounts of Block Practice of theoretically “perfect” mechanics actually make players less adaptable, despite the intentions of the coach. Variability, task complexity and the Challenge Point Principle should all be factored into training in place of mindless block practice.

The Role of the Coach in Managing the Basketball Shooting Training Environment

Coaches play a crucial role in providing basketball shooters with appropriate affordances, primarily through task constraints, to facilitate skill learning. Three key challenges for specialist coaches emerge in managing the training environment:

Challenge 1: Introducing Representativeness and Task Specificity in Shooting Training

Representative learning designs, which closely mimic game situations, have been shown to enhance skill transfer to competition (Renshaw and Chow, 2019). Such designs aim to provide shooters with relevant affordances, integrate motor processes with perceptual-cognitive components, and recreate action fidelity and functionality (Pinder et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2010; Farrow and Robertson, 2017). The “PoST” framework advocates replicating dynamic shooting demands in training to meet individual athlete’s needs.

Example – Shooting in games involves movement and defenders, yet most shooting practice is done stationary and “on-air”. The coaches role is to find solutions that introduce the appropriate level of challenge involving elements that occur within the game.

Challenge 2: Finding a Balance Between Stability and Instability in Shooting Training

Movement adaptability in shooting involves maintaining stability while exploiting fluctuations to develop functional responses to uncertainties (Seifert et al., 2013). Coaches can influence shooters’ self-organization processes by systematically manipulating task constraints to induce coordination changes and enhance their ability to adapt to different shooting situations (Renshaw and Chow, 2019).

Example – Traditional shooting coaching features high volumes of players trying to shoot “a perfect shot”, rather than learning to adapt their shooting mechanics to the imperfect environments and challenges of the game.

Challenge 3: Managing the Level of Information Complexity in Shooting Training

Coaches must manage the complexity of shooting tasks to challenge shooters’ perception-action couplings effectively. This involves modifying task constraints and equipment to vary the level of perceived task complexity and adjusting practice schedules to introduce intra-task and inter-task interference, encouraging shooters to explore the training environment and form stronger perception-action couplings (Davids et al., 2008; Buszard et al., 2017).

Example – Shooting in a game is challenging, and a nearly impossible situation to learn new movement patterns in. Simple situations may be better for learning, but will not transfer habits to a game. The art of coaching is juggling those two opposing dynamics.

In summary, the CLA provides a theoretical framework for understanding skill training, while coaches face challenges in managing the training environment to optimize basketball shooting development.

PART B: PERIODIZATION OF SKILLS TRAINING

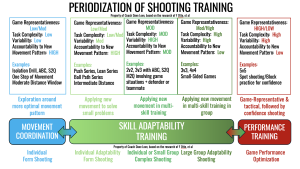

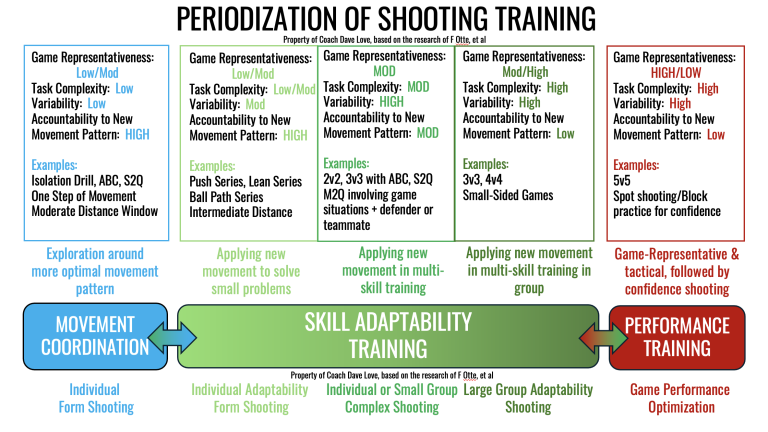

The “Periodization of Skill Training” (PoST) framework, rooted in Newell’s model of motor learning, outlines three main stages: “Coordination Training,” “Skill Adaptability Training,” and “Performance Training.” Coaches are advised to focus on the appropriate stage for each athlete while managing task representativeness and perceived complexity. This framework provides a two-dimensional view, with game-representativeness and task complexity as key factors. Coaches should consider moving between stages to facilitate skill reorganization and optimization processes. Non-linear pedagogy principles support individualized learning pathways, recognizing motor learning as a diverse and multifaceted process.

Each stage of training has specific goals and objectives that the coach needs to be aware of for the training to be valuable, and constraints should be adjusted to help players meet those objectives.

Movement Coordination Training:

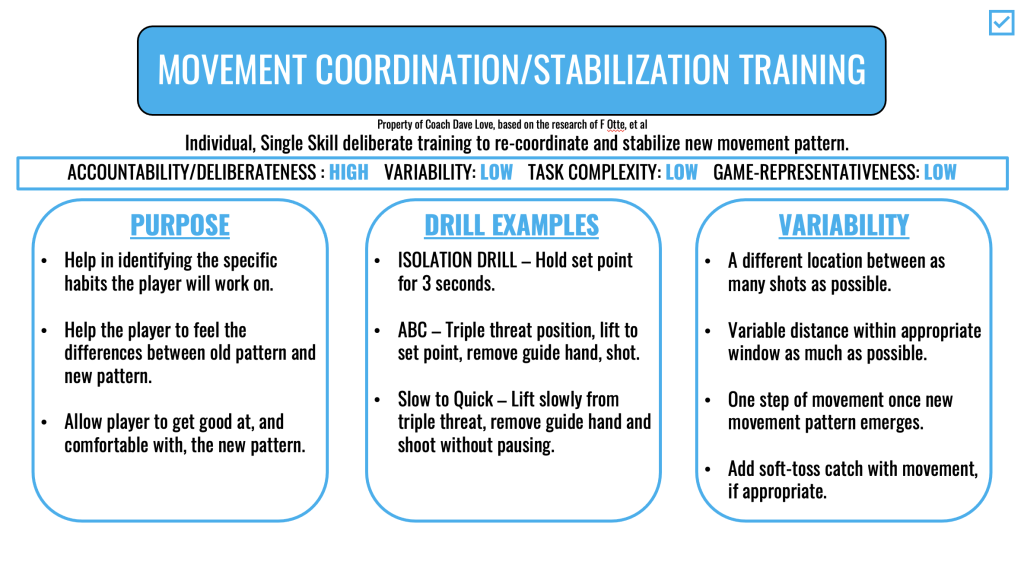

“Coordination Training” marks the initial phase of skill development, emphasizing the exploration of basic movement patterns and stable coordination structures. Athletes in this stage should experience low levels of environmental variability and task complexity, allowing for the acquisition of fundamental movements. Coaches often employ task simplification techniques, creating scaled-down versions of tasks to maintain relevant information-movement couplings while blocking degrees of freedom to match the athlete’s skill level.

In the context of basketball shooting development, this phase focuses on improving foundational movements to guide players towards a more optimal shooting motion. Many players that would benefit from the Movement Coordination/Stabilization phase have habits that are working against them, and the drills of this phase should be designed to get player to explore movements that help players improve their proficiency.

Coaches may use drills with simplified shooting scenarios to help athletes grasp essential techniques and coordination. This stage would most closely resemble what most coaches think of as traditional “form shooting”, but with important differences. Coaches should be focussed on high accountability to specific habits, using constraints on drills to guide players towards those habits, but increasing the amount of variability whenever possible. As athletes demonstrate consistent movement patterns under controlled conditions, coaches can gradually introduce more complex shooting scenarios to progress to the next stage of skill development.

Skill Adaptability Training:

“Skill Adaptability Training” represents the second phase of skill development, focusing on enhancing adaptability, functionality, and robustness of motor skills in dynamic environments. In this stage, athletes are challenged to self-organize and adapt coordinative structures to the complex and representative constraints of performance settings. The emphasis is on cultivating the ability to respond effectively to changing information sources and environmental perturbations.

To facilitate movement variability and promote skill learning, the “PoST” framework proposes three sub-stages:

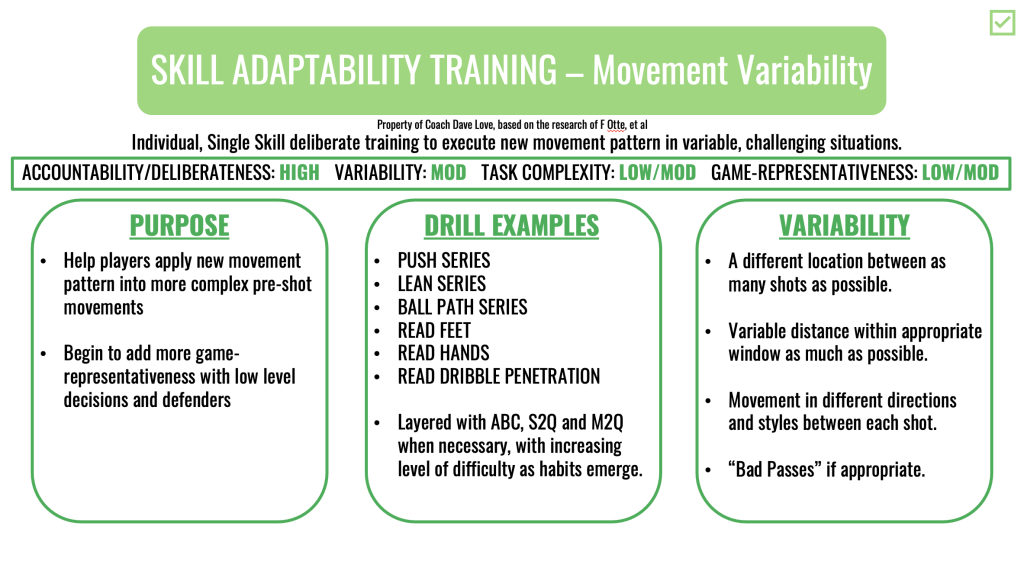

Movement Variability Training: This stage, depicted as the first green section in the framework, emphasizes exploring a wide range of movement patterns and variations. Athletes engage in tasks that introduce variability in movement execution, encouraging them to adapt their skills to different contexts and conditions. Rather than players searching for the most optimal solution, as they were in the coordination phase, players are now learning to get as close to that ideal solution as possible in more challenging situations.

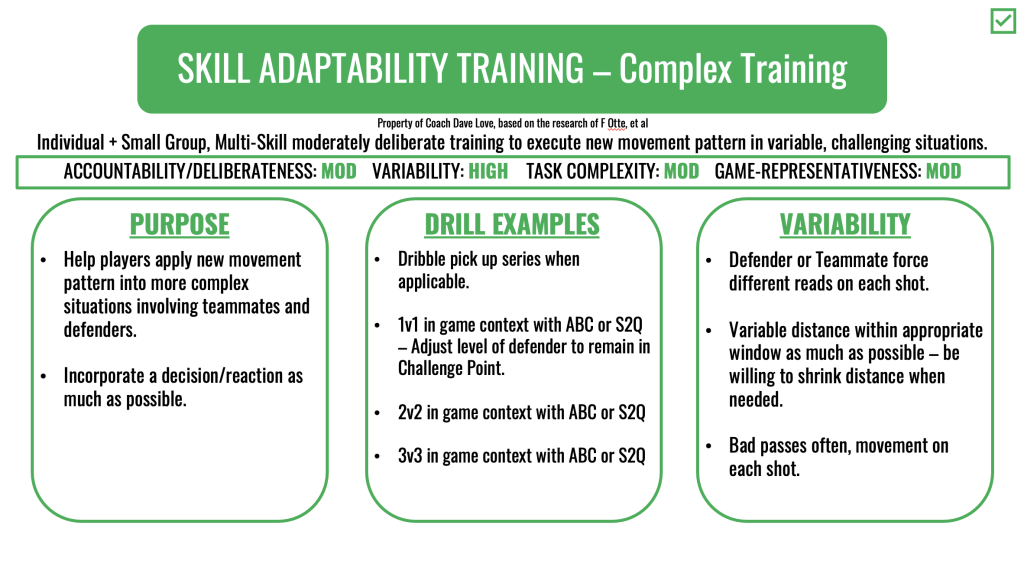

Complex Training: The second green section in the framework represents this stage, where athletes are exposed to increasingly complex and challenging training scenarios. Coaches design drills and exercises that simulate game-like situations with diverse environmental constraints, requiring athletes to develop adaptive strategies and decision-making skills. In this phase players should be incorporating teammates and defenders, as well as coordinating other skills, to force different solutions.

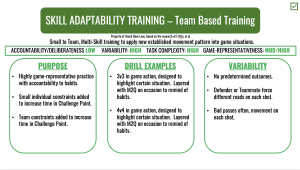

Team-based Training: In the third green section of the framework, athletes participate in training sessions that involve interactions with several teammates and opponents. Team-based drills and simulations provide opportunities for athletes to integrate their individual skills within a collective context, fostering collaboration, communication, and strategic thinking.

Through these sub-stages, coaches aim to cultivate athletes’ ability to adapt and thrive in the dynamic and unpredictable nature of competitive basketball environments.

Performance Training:

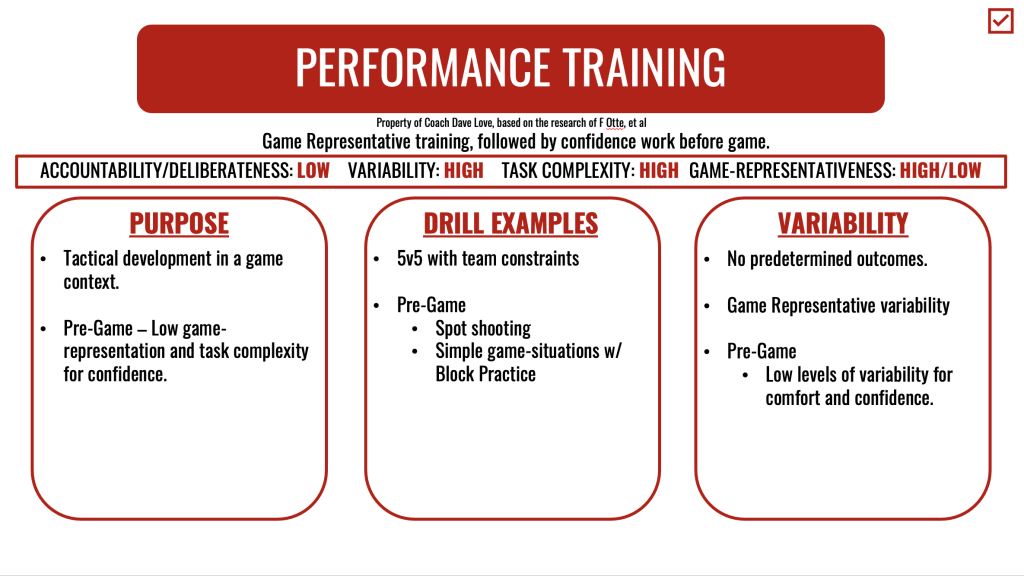

In the third stage of the “PoST” framework, represented by the crimson-colored section on the right, there’s a shift from Newell’s concept of “skill optimization.” While Newell’s model aims at refining skills for adaptability in complex environments, the focus in the “performance training” stage of basketball development is different.

As competition nears (in a typical basketball context, this could be viewed as the day of the game), the goal shifts from skill refinement to maximizing performance efficiency within the competitive setting. Coaches may design training sessions to closely mimic game situations, emphasizing high game-representativeness. For instance, drills might replicate opponent strategies and defensive schemes, with players tasked to adapt accordingly.

Approaching immediate competition (for example, pre-game warm ups or game-day shoot-arounds), athletes prioritize stability and readiness over skill acquisition. They focus on routines and activities aimed at boosting confidence and ensuring they’re mentally and physically prepared. Consequently, in the “performance training” phase, coaches emphasize movement stability and confidence-building rather than introducing new skills. They manage the perceived complexity of tasks and their game-representativeness to ensure players feel fully prepared for the challenges ahead on the basketball court.

This pre-game work typically looks like “spot shooting” that is so common in basketball. Unfortunately, this specific type of training with one specific goal of boosting an athlete’s confidence immediately before a game (while ultimately not worrying about skill development at all) is the most ubiquitous type of practice despite offering limited value to the athlete.

PART C: APPLICATION OF THE "PoST" FRAMEWORK FOR TRAINING PLANNING

In the preceding sections (A and B), we delved into the theoretical underpinnings and structure of the “PoST” framework, highlighting the challenges coaches face in managing training environments. Now, we shift our focus to demonstrating the practical application of this framework for specialist coaches in training periodization and planning. This final section emphasizes two key aspects: (1) the organization of training over the course of multiple months and weeks, referred to as macro- and micro-cycles, respectively; and (2) the structure of individual training sessions, including the arrangement of units within each session.

It is important to note that the PoST framework does not promote linear progress throughout the stages. Coaches will likely transition both forwards and backwards throughout the stages depending on multiple factors, including the coaches observations, the amount of time before competition, and the feels or needs of the player.

Macro-Cycles:

In the context of professional basketball, macro-cycles typically span several months or years and encompass various phases of training aimed at achieving specific objectives. Using the “PoST” framework, a macro-cycle could be structured as follows:

Coordination Training Phase (Early in Off-Season, some practice days):

- Focus on reorganizing and stabilizing flawed movement patterns.

- Utilize drills with low environmental variability and task complexity to establish stable coordination structures.

- Gradually increase the complexity of tasks as players develop movement stability.

Skill Adaptability Training Phase (Later in Off-Season, Most practice days):

- Emphasize skill learning under dynamic and representative constraints.

- Implement movement variability training to enhance adaptability and robustness.

- Progress to complex training drills that simulate game-like scenarios with increasing levels of complexity.

- Integrate team-based training sessions to promote coordination and communication among players.

Performance Training Phase (Leading into season, In Season, Game-Days):

- Shift focus towards maximizing performance efficiency in game situations.

- Design training sessions to closely replicate game conditions, including opponent strategies and defensive schemes.

- Prioritize stability, confidence-building, and readiness for competition.

- Implement athlete-led routines to ensure mental and physical preparedness.

Micro-Cycles:

Within each macro-cycle, micro-cycles represent shorter periods, typically lasting a week, and involve more detailed planning of training sessions. For basketball, micro-cycles could be structured as follows:

Coordination Training Micro-Cycle (2-3 days before game):

- Begin the cycle with drills focusing on basic movements.

- Gradually increase task complexity throughout the cycle while maintaining a focus on movement stability.

- Include feedback sessions to reinforce proper technique and coordination.

Skill Adaptability Training Micro-Cycle (1-2 days before game):

- Start with drills emphasizing movement variability and adaptability in game-like scenarios.

- Progress to more complex training drills with varying constraints to challenge players’ decision-making and coordination.

- Incorporate team-based drills towards the end of the cycle to promote cohesion and communication among players.

Performance Training Micro-Cycle (Day of game):

- Dedicate the early part of the cycle to refining game strategies and tactics through team scrimmages and simulations.

- Focus on stability and readiness in the days leading up to the game, with light practices aimed at maintaining physical conditioning and mental focus.

- Include pre-game routines and rituals to boost confidence and mental preparedness before competition.

By applying the “PoST” framework to training planning, basketball coaches can effectively structure macro- and micro-cycles to optimize skill development, adaptability, and performance readiness leading up to competitions.

APPLICATION OF TRAINING PLANNING FOR SINGLE TRAINING SESSIONS

In applying the “PoST” framework to training planning for single training sessions, coaches can effectively structure each session to target specific skill development objectives while considering individual athlete needs and constraints. Here’s how the framework can be applied to plan single units within a basketball training session:

- Warm-up:

- Begin with a dynamic warm-up led by the coach or a designated player to prepare physically and mentally for the session.

- Incorporate basketball-specific movements to activate relevant muscle groups and movement patterns.

- Complex Training (Part 1):

- Design drills that challenge players to adapt to dynamic and representative constraints.

- Manipulate task constraints such as guide-hand removal, decision-making scenarios, and court positioning to enhance adaptability and decision-making.

- Use defensive constraints to increase task complexity and motor learning demands.

- Complex Training (Part 2):

- Continue with drills focusing on between-skill variability and exploration of movement possibilities.

- Introduce variations in drill setups, physical constraints, or defenders to promote creativity and problem-solving skills.

- Encourage players to experiment with different techniques and strategies to achieve task objectives.

- Individualized Training (Part 3):

- Based on observations from Parts 1 and 2, divide players into smaller groups or individual stations to address specific needs.

- For players who require more fundamental skill development, focus on within-skill variability by refining basic techniques and movements.

- For players who demonstrate proficiency in complex skills, engage them in game-like situations or competitive drills to challenge their decision-making and execution under pressure.

- Integration with Team-Based Training (if applicable):

- Depending on team dynamics and scheduling constraints, integrate individual skill development sessions with team-based training activities.

- Incorporate elements of team offense, defense, and transition play to reinforce skill application within the context of game strategies.

- Emphasize communication, teamwork, and cohesion during team-based drills to foster a collaborative learning environment.

By following this structured approach, basketball coaches can optimize training sessions to promote skill adaptability, decision-making, and overall player development within the framework of the “PoST” model.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In conclusion, the “PoST” framework presented in this blog (and originally conceived by Fabian W. Otte, Sarah-Kate Millar, and Stefanie Klatt, in “Periodization of Skill Training“) offers a practical approach to basketball shooting training periodization, with the potential to assist coaches in designing effective training environments tailored to individual athlete needs. Its strengths lie in its applicability to both macro- and micro-level training planning, as well as its ability to guide the structure of single training sessions and units. By considering the representative demands of competition and athletes’ perceived levels of task complexity, coaches can manipulate the training environment to optimize skill development.

Ultimately, coaches must recognize that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to coaching and learning. It is essential to individualize and periodize skill training based on athletes’ needs, whether working with individual athletes or larger groups. With further refinement and empirical research, the “PoST” framework has the potential to enhance coaching practices and contribute to athlete development across various sports contexts.